The Science Underpinning Change

Den Wandel wissenschaftlich untermauern

Podcast in English: Saskia van Stein on 15th August 2023

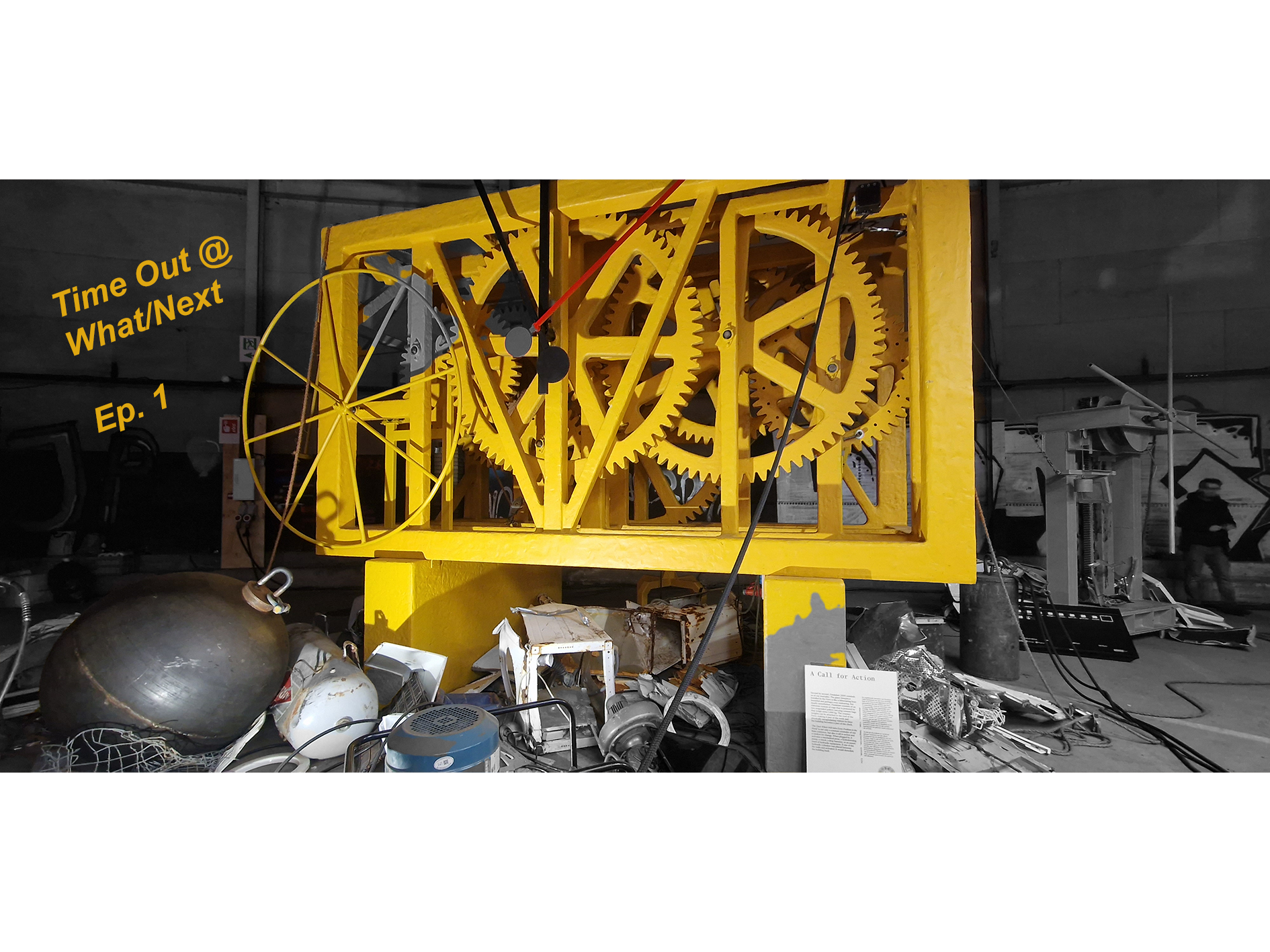

Understanding and showing the relevance of time to people of diverse ages and backgrounds can be not only a theoretical but a creative and cultural challenge. In this inaugural interview with Saska van Stein, the Time Out team uncover the initial processes and thinking that enabled and inspired the International Architecture Biënnale Rotterdam to organize, curate, and host the 2022 biennale It’s About Time.

Die Relevanz von Zeit für Menschen unterschiedlichen Alters und Hintergrunds zu verstehen und aufzuzeigen, kann nicht nur eine theoretische, sondern auch eine kreative und kulturelle Herausforderung sein. In diesem einführenden Interview mit Saska van Stein deckt das Time Out-Team die anfänglichen Prozesse und Überlegungen auf, die die der Internationalen Architekturbiennale Rotterdam, die Biennale It’s About Time 2022 zu organisieren, zu kuratieren und auszurichten.

RAC: So, thank you to Saskia van Stein for joining us today on our first and inaugural episode for Time Out at What/Next. My name is Robin Chang and I am a postdoc scholar at the Chair for Planning Theory and Urban Development at the Faculty of Architecture in RWTH Aachen University and I have with me today Manila de Iuliis as well, who is also a practitioner and researcher who has worked with the topics of time and temporality since her PhD back in the UK at Salford University. She brings experiences in public administration and planning in the Italian context as well as in industry in the German and Dutch context, whereas I come from Canada originally, so I have practical experiences in Canadian planning but have also more recently through my research been looking at time and temporality. So, today we have Saskia van Stein with us today and I’m really excited to be able to include her and introduce her. I know that Saskia, you probably will be able to say a few words about yourself, but you have most recently, or at least last year, for the International Architectural Biennale in Rotterdam put together a fantastic program. In fact, I have even still the pamphlet here for the exhibit. Actually, this is upside down. It’s about time. So, we’re really excited to be able to learn about you as a person but also the thinking and the creative energy that you as well as other colleagues and thinkers put into this exhibit and how this can actually give us reason to have a time out in our busy lives but also in the philosophies of how we want to live and actually, yeah, walk the talk of being sustainable or contributing to liveable and healthy communities, globally. So, I’m going to ask and put you on the spot if you don’t mind just saying a few words about yourself, your background and where you’re at now today.

SvS: Fabulous. Thank you so much for the invitation, first of all. Very nice to meet you. I just came back from holidays, so time somehow is sticky or even liquid in my reality. I hope to find the right words because I somehow feel that I’m grasping with words, being in a void of sort of thinking about my near future for the last three weeks. That said, my past – I was picked up by Mr. Aaron Betsky back in 2001 while organizing debates in the city of Rotterdam where I’m currently residing – also where the office of the International Architecture Biennial’s office is on the periphery, literally located on the threshold between harbour and city. But, back in the day, I was organizing Archi-cases. Yes. So, on the socio-political topics and how architecture should or could have a certain kind of agency. And he literally said, you seem to have quite an opinion, come and curate the show. And I stayed nine years. So, my first steps in curating were in the Netherlands Architecture Institute – now Het Nieuwe Instituut. After which I started up in Maastricht, very close to Aachen, Bureau Europa, with a micro budget, trying to look into what European identity could mean, both for the built environment as well as a sort of humanitarian position. I was then asked to start as head of one of the masters of the Design Academy, which I titled Critical Inquiry Lab, where we aim to centre stage research-driven design as a practice. So, it’s not an object, but literally the research that would result to either the what or the how in forwarding current, well, I would nearly say societal crises, but we’ll get to that maybe later on. Headhunted for this marvellous function about, or I should say tenure, yeah, about one and a half year ago. So, I really had a crash course in jumping in, rewriting the policy plan for the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam, which was celebrating its 20th edition. Maybe sort of situating very shortly the Biennale itself, sprouted out of the ambition in 2002 by Kristin Feiereiss, now director of AEDES in Berlin, to have a vehicle to get international perspectives into the Dutch cultural landscape. So, she first initiated the Dutch pavilion or was actively programming that in the Venice Biennale, and this was the vehicle to get those international voices back in. Now, fast forward, obviously the cultural landscape has changed. The Dutch cultural landscape has drastically changed. We might come to speak about that because I feel that we are actually still trying to formulate an answer after the Super Dutch, glorifying years. Happy people in the field. And as I was, yeah, maybe just to sort of very briefly, I’m in juries and committees, and I’m one of those people that also moderates as a hobby because it’s my way of thinking out loud. I’ll keep it at that because we have a lot to share or speak about. I’ll wait for the first and second question.

RAC: Thank you so much for that introduction. Yeah, it definitely sets a good tone and canvas to understand where you come from… the experiences and the insights. And it clarifies a little bit the reasons for why you were headhunted for, you know, the position at IABR and how you’ve taken a different tack to it. I do find it very opportune that, and timely, that for the 20th anniversary, that the exhibit that was put together It’s About Time – I found, so I did attend last year, I’m outing myself as participant and someone who has gone through that embodied and cerebral experience of trying to explore and experience what time and temporality meant in that exhibit. And I did find myself that it was both at once a kind of internal orientation to reflect on what types of actions people could do, perhaps, in some way, a projection of this Dutch reorientation, looking back at the glorified years of design and architectural kind of philosophies. But at the same time, it was also a bit of a call to arms, too. And I did notice that the impulse you guys drew on history. So, you drew on the impulse of the 1972 publication The Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome but that you guys also had a very explicit and very much emphasized hopeful perspective about how action and interaction could inform an architecture for change. So, we’ve prepared a couple of questions to try to jump into your mind and thinking about time and temporality and how that relates to your work and practice and pedagogy, as we’ve learned now. So, we’ll start with the first one: so, time and specifically, in my opinion, speed. There was a sense of urgency, this action or interaction in the moment of today. It was something that you, as well as your team, problematized through the program. So, we’re curious about that thought process that went into trying to shape and craft that experience – time with temporalities – and perhaps maybe, if I can nudge a little bit, that kind of accelerated or urgent sense of how we deal with time and temporalities. So, how was that for your directional as well as curatorial team? What were the types of conversations that went into striking up that type of energy?

SvS: Thank you. Yes, so maybe just to sort of emphasize how the structure of the biennial works, so people have a bit of a feel. Obviously, it’s a two-year program and we centre stage a quite bombastic monumental word, for instance ‘The Flood,’ which was done by West 8, Ardiaan Geuze or ‘Power,’ which was done by Maarten Hajer who’s a sociologist at the Utrecht University. So just to say that these words to sort of capture the theme, that was quite random, but we used two years to build up to it. And this was in fact compressed to nine months, yet I was already confronted to the appointment of Mr. Derk Loorbach, who is a scientist, and he is specialized in transitions that would be the science underpinning change. That comes with a deep understanding of history and a projection, one could say, into the near future with then using backcasting strategies in order to see or understand where the future will take us. You might know in futurology we have different strategies, the probable, the possible, the desirable and the wild card, these are different degrees f change in our near future(s). And my first conversations, well, first of all, I was met with him, so I had to deal with him. There were two scenarios, either fire or sort of bend things, which is a bit more my method. So, we bended, let’s say, the main theory that he is known for is called the X-curve.

So, what is in decline and what is on the rise in terms of really large systemic changes that are manifesting.

And these changes, obviously, they come with planetary realities, with economic realities, but they also come with a social and cultural change. And it dawned on me to a certain extent that his transition theories in X-curve had to do with that threshold of change and our fear for this change or the lack of political will around the changes that we see on the horizon.

Saskia van Stein

Obviously, I haven’t said the word climate change yet, but due to and under pressure of the climate realities. And I’ve never – it’s actually interesting that you put the word speed out there, because I use words such as temporality, velocities and acceleration. So, I would have to really reflect on speed, but because to me, time actually also looks back at history but you’re the academic on the word. Maybe I won’t venture into that notion of speed but the Futurist Manifesto comes to mind, dealing a lot with industrialization and upping the game. But back to your question, I thought it would be interesting to propose a decentralized model, because I think the future will be decentralized, oriented towards, let’s say, technological and social will have to remit in a more profound manner. But for the curatorial team I wanted to propose someone from the practice, and I wanted to really start with the land, literally. So, I invite a landscape architect who brings that knowledge in, that was Peter Veenstra (LOLA). And then I was reflecting if cultural institutions, knowledge institutions as the one I’ve come to run, are in fact, also part of the problem as I was questioning this idea of newness in relation to speed in culture, and the eagerness for newness in relationship to the growth paradigm. This is why I thought, let’s bring in architecture history. So just to sort of explain the thinking behind the team. So, this is where Véronique Patteeuw and Léa-Catherine Szacka play a role. Together, with them, we started off this question on which changes are manifesting within the practice of the architectural discipline. During these conversations we really looked at and were trying to understand the role of the architectural practice, in relation to the current climate crisis. And if which kind of attitude and temporalities would have to come into the design practice in order to truly come up with a more sustainable way of understanding the practice. Did I answer every question? Probably not. Then it dawned on us that the Club of Rome, in fact was, and for those you introduced it already, very briefly, but they came up with the first, let’s say, computational models, what one could think of scenarios, which is very close to the thinking of Professor Dr. Loorbach. These 11 scenarios that they investigated, pollution, population, food, (industrial) output and natural materials, a few of these fundamental parameters to investigate where we will be in 2072. We’re halfway, and how are we doing in relation to their prognosis, one could say, although they actually rejected the word prognosis, but I won’t get into the nitty-gritty, but the ‘If we do not do anything for dummies-scenario’ is what we’re living today. So, what we aimed with the exhibition was a backdrop of 100 years of policy making, popular movement, experimentation in the field, architectural material, bottom-up building and so on, we’ll probably get into the exhibition in greater detail but it was in fact to investigate where are we now? Is it all gloom and doom? Because we wanted to debunk a little bit this sense if disempowerment, I would say, it’s a political choice to harvest on the fear for the systemic changes we are confronted with, in order to prevent or – one could have a vision, one could have a direction, which is much more hopeful. We aimed to create a landscape of possibilities with over 170 photos, models, films and books historical examples representing 75 projects. And these projects were divided in the triple AAA chapters, as we call them (which is, of course, a little nudge to the banking system, its validation system): the accelerator, the activist, and the ancestor. So, I think answering the last question, and maybe we have to pick up on a few of these examples to make it palpable for the audience or for the article that we have, we have images, obviously. Is that the response was that people were in fact shocked that there was already so much done. Of course, Greta Thunberg is now our Joan of Arc, but so many others have been paving the way for this conversation. And one of my most inspiring, but also cynical awareness’s is that it was President Jimmy Carter who put solar panels on the White House when he came to office. And when Reagan set foot, immediately had them removed and then introduced the rhetoric of green growth. Well, there you have it. It’s the rhetoric we’re still living in the current model. I’m not sure if I answered all your questions, Robin, but feel free to throw one in again.

RAC: Yeah, Saskia, no, you’ve gone above and beyond that, I think. Probably with the time that we have. So, I would dig a little bit deeper – both Manila as well as myself. This is a chance to have a short conversation, a timeout, a break during our daily lives, our busy lives, to think about time and temporality. And you’ve already given a lot to think about. I find it also really interesting that the depth of the work that was built on the lives of many giants, as well as regular citizens, you guys have picked up on that. And this was definitely clear at the exhibit. I remember walking through the various rooms and just completely being awestruck by the various types of material, media, the text, the content, the insights, even the maquettes, so the smaller types of models and how creative and diverse they were. One particular one, I think, was dealing with flooding. And it was interactive in that you could actually it plug in and fill it up with water to visualize, to some extent, project, as was intended, perhaps, or is a motivation behind some of the thinking and theories from Derk Loorbach. But what I find also very interesting is that you’ve given us, through the exhibit, as well as participants, tangible strategies behind the accelerator, the ancestor, as well as the activist, to think about how change, constructive change, for a more sustainable future is actually within our hands. But it’s probably a rather individual choice that, of course, is guided and steered to some extent by the policies that were dealt with, trends, the zeitgeist that we’re living in the moment. But that does come down to us as individuals making choices about how we act, how we commit to these actions, how we interact with others, and how we truly walk that talk and provide that sense of agency, not as just a rhetoric, as Reagan did following Carter. But as a true and committed act for the future. So, I think maybe what I’d like to do is dig into some of your more personal type of reflections on that experience, coming out of that. I think Manila, she actually has the last question that we wanted to dig into in terms of you as a person and how you experienced that. Manila, do you want to take it away?

MdI: Yes, yes. Thank you, Saskia, very, very interesting. Wow, I could listen to you for all day. Thank you.

SvS: Grazie.

MdI: Prego. So, my question is, how did this experience of the Biennale change your relationship to time and speed? I mean, you embody several different intersecting perspectives, because you’re a woman, you’re a director, you’re a researcher, an educator. And these perspectives are, of course, they can amplify your vision, but they sometimes can also be conflicting. So, can you tell us a little bit more? How did this experience touch you?

SvS: I’m interested by the word conflicting. Maybe I’m just a very non-linear person by default. It’s an interesting question. Well, first of all, I want to emphasize this was truly teamwork. One of the aspects I feel very much attached to, is that the exhibition was held in a former gas holder. This is the kind of thinking very core to my practice, that things have to somehow be just. And to be in a ruin of a former container of a fossil material felt like a right way to exhibit. And everything that was in the exhibition was connected to the land, to agriculture more precisely and everything was borrowed. So, the sand, the roosters and the walls and everything was borrowed and temporarily taken out of their ‘regular’ material infrastructure. We actually embodied the way of thinking in the way of working and the way the profession could go forward in the exhibition, hopefully.

But returning to your question, Manila, I would say that I draw the most inspiration from being around young people. As I already mentioned, I’m in now co-heading the MA department with Patricia Reed, an artist and theoretician from Berlin, with her I have conversations on education, on cosmologies, on ecologies, so both the planet and the body as an ecology, right? I mean, we are a whole vat, if I for lack of a better word of different gut flora. And, you know, there’s so much information on the relationship of the human and the more-than-human, not even around us, but also in us, we are relational beings. So, this kind of thinking, how we situate ourselves, not above the world, but in it has been very influential for my work.

Not only in the Dutch context but also globally, I would say, we see a fragmented landscape in architecture. Now, architecture we know is slow to stick into the semantics of speed and time. But we also see a fragmented landscape because there’s no new narrative introduced at the moment. Everything regarding building and planning went to the markets, but even now the market is searching for what are the ways forward, which is a very interesting time to in fact, reintroduce the question–beyond the rhetoric of nostalgia–how architecture can play a role in future visualizations, or visualizing a future that is desirable.

Saskia van Stein

So that’s why the theme of the next biennial is hope because we need to underpin constructions of hope, in order for all of us to not start blaming each other for the planetary disbalance that we’re currently living. And it’s going to get worse. And of course, we talk about all of this as a planetary disaster, but it will become a humanitarian disaster. It is actually, already. I shouldn’t say becoming it is. So, returning to your question,

I think what I try to bring into the discipline are questions related to the consequences of the material cultures that we in architecture extract, so architecture as climate, right? I mean, it is material, it is also immaterial. So where are the strategies that we should reflect upon? These material cultures and extraction are often rooted in deep colonial histories. So that asks of us to revisit and rewrite those histories.

Saskia van Stein

You mentioned me being a woman. Yes, it’s a very active conversation at the moment – the role of all different identities and how we are (under) represented and how we can debunk this singular, one way of looking at history. This also asks for a different language. The fact that we had the word ‘hole in the ozone layer’ – literally, enabled us to communicate and visualize it. That was the beginning and the turning point for legislation to come into place and for people to change their behaviour. As for my inspiration, I draw from, without sounding too exotic but I didn’t grow up in the Netherlands, I grew up in Dar es Salaam in East Africa and Baghdad in Iraq and this has come to my attention very late now in my early 50s; in other words, this experience has really manifested recently in myself. Being white and being Western is such a dominant narrative. I’m preaching to the already converted, but I do believe that the architectures that we produce can facilitate that conversation and can facilitate the male, female, or those-who-define-differently conversations, in the public space. Who’s talking about public domain anymore? I mean, there are a lot of questions we can pick up on. And I look forward to being part of that conversation that spans from the politics of design to different forms and temporalities. So, returning to your initial question, I believe that each architect, designer, urban planner has to maybe question where they relate. And obviously, we are not sometimes an activist, sometimes I’m an accelerator, right? But how do we weave these different temporalities, these different design attitudes, both material and immaterial into our practice. And then these topics that we’ve been talking about will come as a second nature. And maybe listen a bit more instead of answering questions, but I try to do to the best of my abilities.

MdI: Thank you, Saskia.

RAC: Yes, indeed, Saskia. Thank you so much for giving us much food for thought to listen to today. And also some insight moving into practice – how we can rethink and reconstruct and reorient and perhaps reposition ourselves, because I do think that over time, as you’ve pointed out, this meshing of different types of roles or mentalities and attitudes we might have to take on, it’s not purely ancestor activists or accelerator, it could be a mix of both, it can flux over time as well. And so how we do consider and contemplate that balance of these types of positionalities or attitudes is something that we have to be very aware of and reflect on constantly.

SvS: Exactly, maybe if I can very briefly touch on that. It also,

I mentioned the semantics, but I think it also demands a different knowledge system. We have to acknowledge that our cultures and our knowledge systems are also quite problematic in a way. So, I say our, but I speak from a Western perspective, how can I try to liberate myself from that perspective, this poses questions to the locality and context.

Saskia van Stein

And we see, for instance, you mentioned being from Canadian descent, we see that the US and the Canadian rhetoric is much further than the Western in acknowledging Indigenous cultures, knowledge, and their right to land.

I’m trying to understand what does it mean, this locality, how to re-appreciate the knowledges that are embedded there in the land, in a context, that we embody differently, without becoming sort of nostalgic. So, there’s a sort of very interesting new balancing act going on, on how to be maybe planetary, open by heart, but locally rooted, I don’t know. And what does that mean for cultural institutes, for being designers, for all of us, again, I find it a very challenging moment in time.

Saskia van Stein

And I’ve never thought that we, for instance, are now starting a carbon college, literally as a cultural institute, going into workshops on how to understand CO2 in your designer practice. I don’t want to start another conversation, because you know, when to close, but just to say that it also poses questions to all of us.

RAC: Absolutely. Thank you so much for these insights in terms of more of the psychological and theoretical realm of how we can rethink, reinvigorate our actions or interactions. Yeah, I highly encourage that the listeners or the future listeners who will take a bit of a time out just to listen to our conversation today will take the chance to go and visit the next exhibit that has a much more hopeful type of stance and positioning in Rotterdam. Thank you again Saskia van Stein for your time today, for your thoughts for this edition of Time Out.

SvS: Pleasure. Thank you, Robin. Thank you, Manila.

Saskia van Stein is curator, educator, moderator, and the General and Artistic Director for the International Architecture Biënnale Rotterdam (IABR). Since joining the IABR in 2021, she has become a prominent and careful shaper of content and questions to help urban designer, practitioners, and dwellers think deeply about built and lived landscapes of possibilities.